Deep listening, profound disruption

I worked for many years with someone who was the most powerful listener I have ever experienced. He possessed a rare combination of paying full attention to whatever you were saying and resisting the urge to add his own views and beliefs. He listened with the attention a cat gives when stalking its prey; in that moment nothing was more important, nothing was allowed to distract. The quality of his listening affected the quality of my speaking; my words felt important, each one treated as precious. It’s a small step to take from feeling your words are important to feeling you matter. Being made to feel you matter … what a wonderfully affirming act.

He made me feel heard in a way that felt rare to me. It had the impact of saying much more than I intended. I found myself disclosing information I didn’t think I would; sometimes the information I disclosed was new to me. I found myself saying things I hadn’t voiced before, in the process learning something about myself. This was often enormously helpful; his listening allowed me to understand my own thinking much better than when it was trapped silently in the echo-chamber of my thoughts.

Then when I thought I had said it all, when I didn’t think I had anything left to say, he would replay what he had heard or ask a simple question, validating my thinking, proving that he had listened, allowing me to change something (often important) in my views which had, until that point, felt so firm.

You might be rolling your eyes at this point, the importance of listening is obvious isn’t it? Wasn’t it covered comprehensively on the first management training course anyone ever attended? Yes and no. It is obvious, we know it’s important but that does not necessarily mean we do it well. Common practice is not the same as common sense. How accurately do we evaluate our own capability as a listener? How strong is our belief in the immense value it can bring? Most of the time we assume we do it well, rather like our belief that we possess a good sense of humour and are above-average drivers; we tick the mental box and move on.

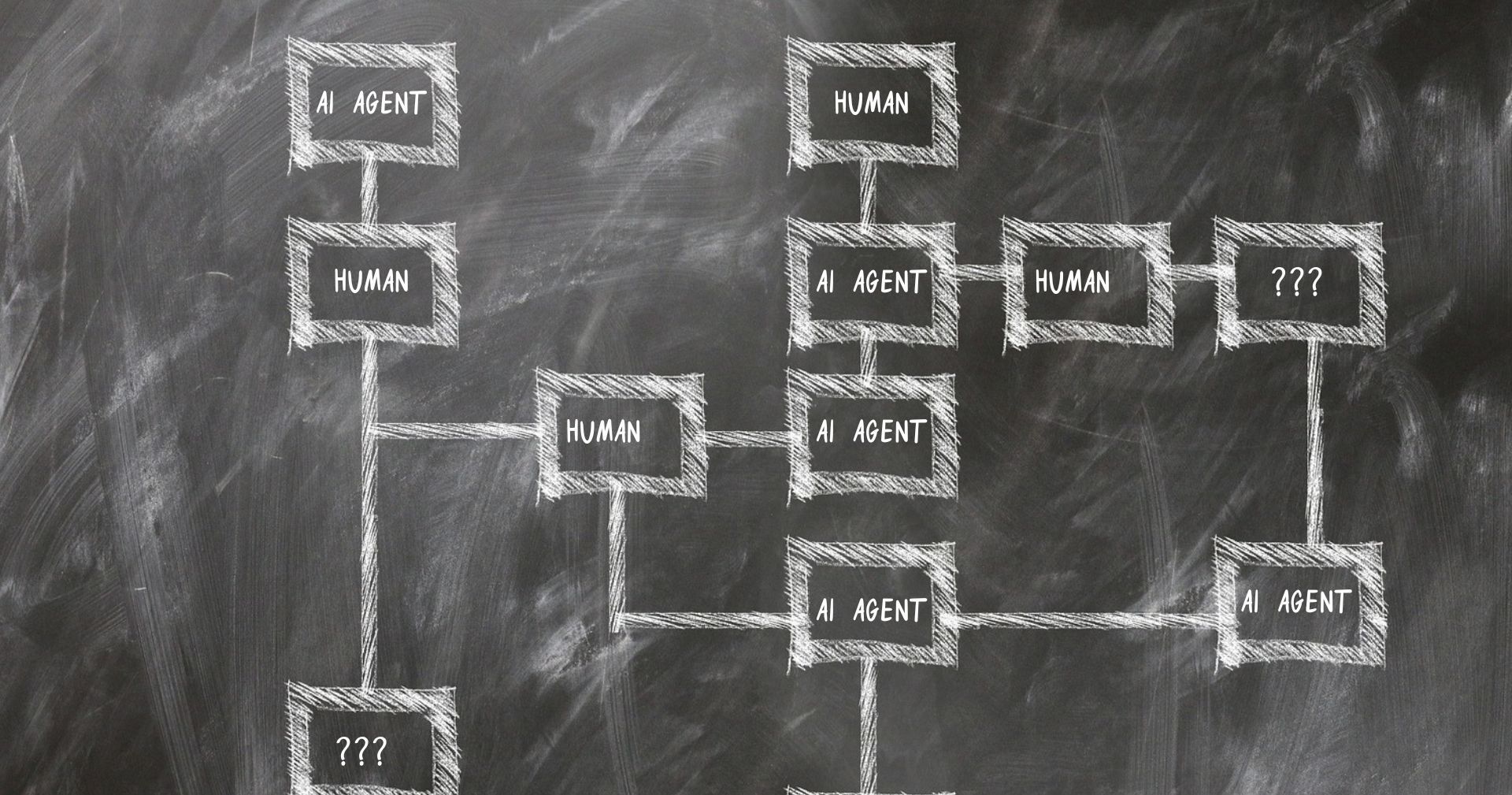

There is a further step that can amplify the impact of listening in organisations – action. The evidence that our words are important to leaders is reinforced when we see something happen as a result. However, there is a twist best exemplified by a version of the following slogan I often see: ‘you said, we did’. In many ways this is powerful, an articulation of the importance of speaking up and being listened to. But the danger is that it reinforces the thing most modern organisational cultures want to escape – the parent-child relationship which is the antithesis of empowerment.

Once my colleague demonstrated he really understood my perspective, his great skill was to resist the urge to resolve things for me. At first, I found this deeply frustrating; he was more senior, he had more power to change things, why didn’t he step in and sort things out? I guess because he understood that by doing so he would be limiting my development, my growth and my ability to create change. Isn’t this what we want? To feel empowered. Think how powerful it could have been if all my colleagues had shared a similar experience and the whole organisation was populated by people who felt as I did after being listened to.

In the previous blog I wrote about the difficulty of bringing about cultural change in complex systems, i.e. organisations, and the value of disturbance as a catalyst for change. The form of listening I have described here is in itself a disturbance; it has the potential to be transformative individually and even more potential collectively. In many organisations, hierarchy, fear, our egos and general busyness are barriers to paying attention; the seemingly simple act of listening can take some doing. But who knows where it might lead? ‘Big doors swing on small hinges’.