Thinking about thinking

When my good friend and colleague Nick introduced me to the ideas of Daniel Kahneman more than a decade ago the significance of his work completely eluded me. It seemed peripheral to the work I do; whereas now, with a deeper understanding and more thought from me (ironic I know!), I see Kahneman’s work and the work of Amy Edmondson (about which more later in this blog) as central to it.

Kahneman’s research (which was done largely in partnership with Amos Tversky) resulted in the best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow and a Nobel Prize. Until Kahneman and Tversky examined the way we make judgements and decisions in uncertain situations, the prevailing scientific belief was that human beings were essentially logical and rational. Their revelations of our unconscious biases and ‘heuristics’ (the unconscious simplifying rules of thumb we apply in order to come to a decision) were controversial and unpopular amongst many psychologists and economists until the point was proven in so many different ways it could no longer be denied. Often the way we make judgements through heuristics is helpful, but equally they demonstrated that it can lead to systematic, predictable and significant errors.

As an aside, quite apart from the brilliance of their work, their collaboration and ways of working together (‘I did the best thinking of my life on leisurely walks with Amos’) is a fascinating story in itself, brilliantly told by Michael Lewis in The Undoing Project. Their characters were entirely different (Tversky believed his own ideas were always right; Kahneman believed his own ideas were always wrong) and the way they created new ideas beyond which neither could have produced individually, is an inspirational example of harnessing difference. Kahneman described the way they worked as ‘a conversation … a shared mind that was superior to our individual minds’.

One example of their work, which might well feel obvious now, was to test the impact the framing of statements and questions has on our decisions (something which nudge theory exploits). For example, surgeons who describe an operation as having a 90% survival rate have a far higher consent rate from prospective patients than if the operation is described as having a 10% fatality rate.

We jump to conclusions, make judgements and know the answer without noticing we’ve done this. This is often helpful; it keeps us safe and allows us to do things quickly. But it also limits us and stops us seeing things, like alternative approaches, fresh interpretations or a better understanding.

Kahneman described our thinking as having two different modes, System 1 and System 2. He points out that both of them are fallible and both are useful. System 1 is our fast-thinking automatic response; our thoughts appear without us going through the effort of thinking. System 2 is slower and takes more energy; we subconsciously conserve our use of it for just that reason. We don’t like to invoke System 2 unless it is necessary to do so, such as when we encounter danger.

There are many differences between these two modes, one of the most important being that System 1 fits what we experience into the simplest narrative we can find; in that mode we look for certainty and coherence. It is common for us to answer a question we know how to answer rather than the actual question we need to address; or to downgrade or dismiss information that contradicts our story. System 2 on the other hand can cope with nuance, and crucially can ask the question ‘what am I missing?’. System 2 doesn’t have to be right.

Our individual thinking is subject to distortion and influence that sit largely outside our awareness. Unless we actively guard against this (sometimes by involving other people in our thinking processes) we fall prey to it again and again.

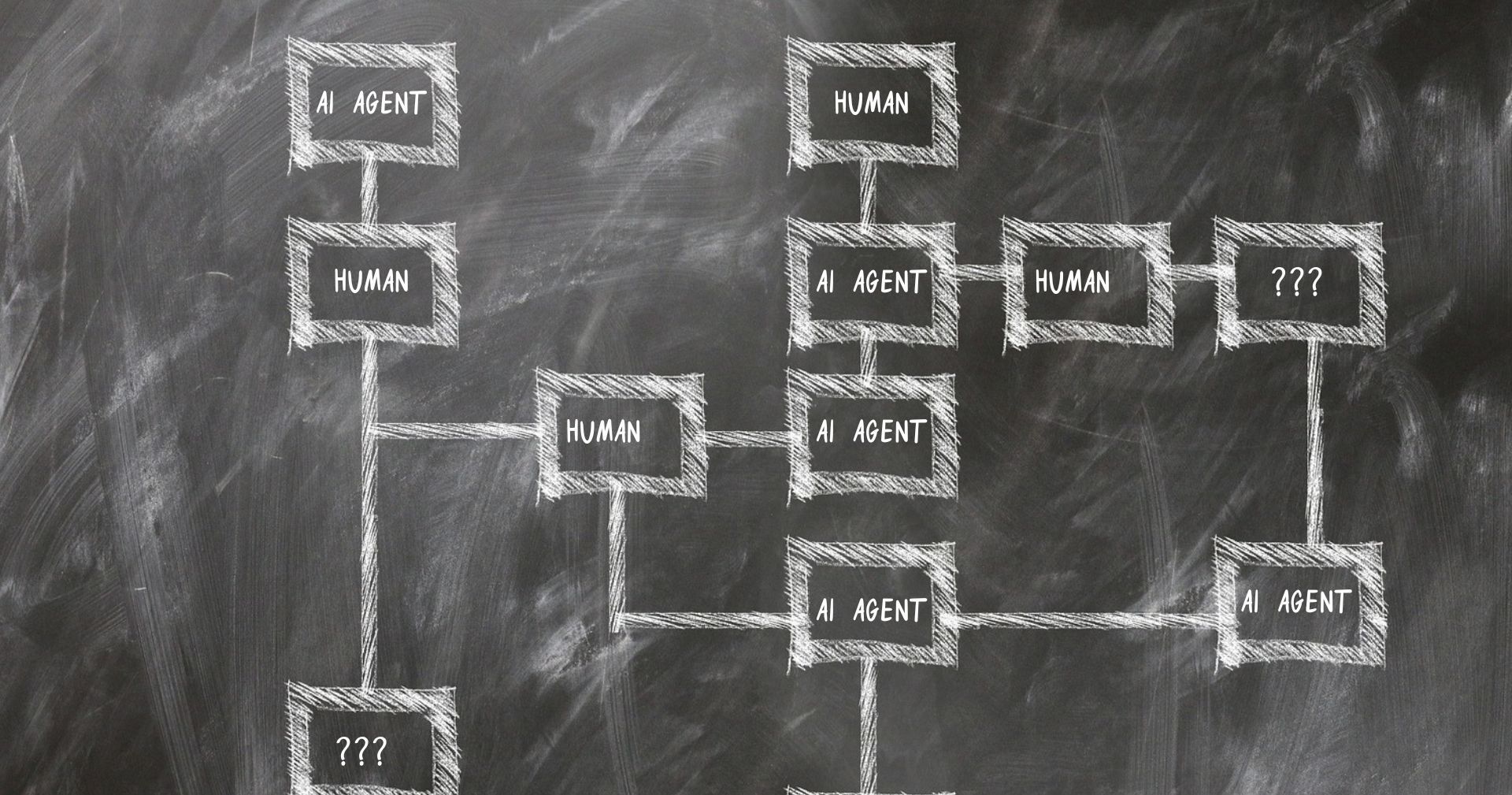

So perhaps the answer is simply to work at problems together in groups? However, the social pressure and norms in groups make it unlikely our conversations will be as unfiltered and undistorted as we would like. This is where the work of Amy Edmondson

on psychological safety (which stemmed from looking at death rates in hospitals) is revealing in terms of the impact a lack of psychological safety can have, particularly in groups with a mix of hierarchy. She memorably talks about the ‘need to reduce the cost of speaking up and increase the cost of keeping quiet’ in groups which are working on complex problems. The movie mogul Sam Goldwyn expressed the difficulty brilliantly when he said, ‘I don’t want to be surrounded by yes men. I want everyone to speak up ... even if it costs them their job’. I argue that the most important task of leadership is to create psychologically safe environments, without which the flow of information and ideas is hampered.

There is however, a paradox to consider. Without sufficient cognitive strain, it’s likely that System 1 will prevail; there is no need to wake-up lazy System 2 in situations that do not merit it. We are naturally drawn towards cognitive ease and are biologically programmed not to waste our energy exerting System 2 when System 1 can handle the situation perfectly well. It follows therefore that it’s possible for situations to feel too safe and easy; if there is no grit in the oyster, the risk becomes one of ‘System 1 group think’. Psychologically safe environments have to include sufficient challenge to invoke our System 2.

Our cognitive load is influenced by many factors including the way information is presented, the familiarity of the topic, our mood and the social setting. Cognitive ease allows our System 1 thinking to prevail without any need for the intervention of System 2. When we are in a state of cognitive ease our intuition and creativity are more readily expressed but we run the risk of failing to spot our own errors and biases. Conversely, when we experience cognitive strain which invokes System 2, we benefit from applying more diligence to our thinking and are more likely to question our assumptions and beliefs. However, the cost of this can be a loss of ‘flow’, something which is often the hallmark of a great conversation.

When we combine our individual thinking errors with the additional implications of working in a group, then it isn’t surprising that working on really difficult (by which I mean uncertain and complex) problems like strategy is so tough and (in my experience) so frequently disappointing in terms of outcome.

Too often strategy is treated as a technical problem which can ignore the communal and individual thinking processes involved. Unless we pay more attention to our own thinking and the social conditions in which the work is taking place, we are likely to fall a long way short of what might be possible; if we paid active attention to both these factors and established approaches to compensate for them, we could produce far better results. For important decisions, it’s imperative we design processes which contain discipline and rigour to counteract the flaws in our intuitive thought and establish environments which feel safe enough for uninhibited dialogue, but not so cosy that System 2 thinking is avoided. Strategy is challenging enough without us tripping ourselves up and in Kahneman’s words ‘being blind to our own blindness’.