Listening, a secret weapon

Experiences of working with different organisations on cultural change have underlined the intimidating scale of the task. I often hear comments from leaders such as: ‘It’s too large to seem possible’; ‘We need a big outcome, we don’t know where to start’; ‘We’ve made so many attempts in the past that we’ve lost belief in the approaches we use’.

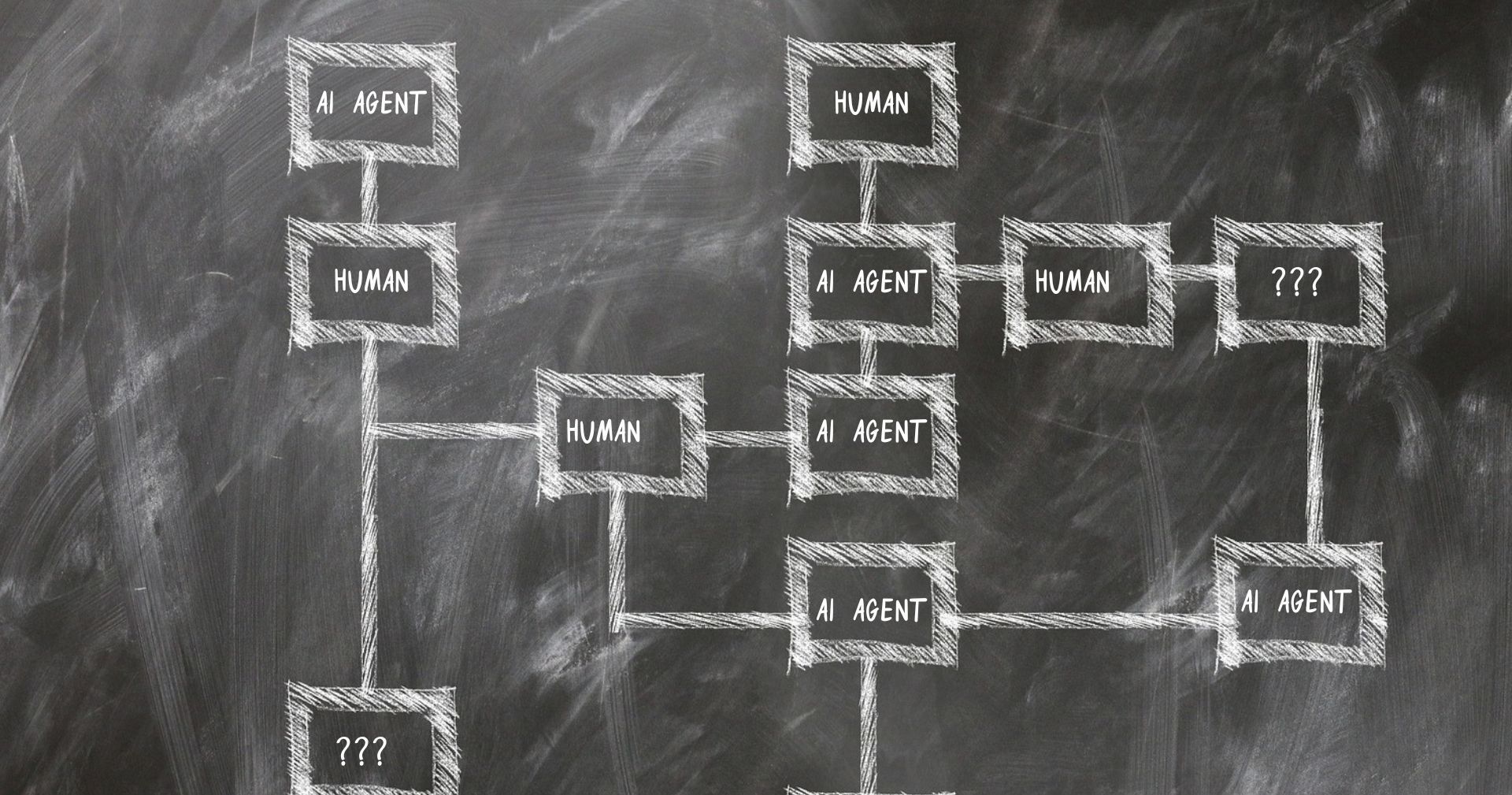

One of the things which exacerbates the situation is that by regarding organisations as machines (a common metaphor), and regarding change as a mechanical, predictable process, we become despondent when we discover it just isn’t like that, ‘the map is not the territory’. It isn’t simply a matter of defining what is wanted in terms of culture, communicating it, issuing instructions and then watching it happen. It’s more helpful to accept organisations for the complex systems they are, given that getting anything done involves a multitude of small human interactions combining in ways which are unpredictable and uncontrollable. We live our lives in ‘the territory’, however different it is from the map we might have expected.

The characteristics of complex systems require a willingness to relinquish the belief you can control what happens AND at the same time hold on to the possibility that systems can reach a tipping point in terms of change; sometimes actions which are seemingly small can enable new patterns (i.e. culture) to emerge; what we don’t know is when or how this will happen. This is challenging to leaders who often believe, and are rewarded on, the ability to control. As a colleague of mine used to be say, ‘it’s tough to be in charge but not in control’.

Complex systems do not lend themselves to predictability, but on the other hand small actions can become amplified and disturb embedded patterns behaviour; the frustrating part is not knowing which of these might produce the desired effect, hence the need to try things and to notice with great attention what the impact is. If the impact moves things in the desired direction culturally then you know to do more of it. If on the other hand the impact does not, try something different.

An example of a cultural tipping point being reached was the introduction of the 2p charge in supermarkets for plastic carrier bags. It was an experiment, the brave step of trying something different, which has drastically reduced the number of plastic bags that are in circulation. Who would have thought such a massive impact, which has transcended geography, socio-economic class and age could have been achieved through such a seemingly insignificant change? You never know what the difference will be that will make the difference.

Much organisational change energy is devoted to the communication of change in the form of announcements, internal publicity campaigns and training. This is understandable given that it is something we can control, perhaps in this way making us feel more powerful as leaders. This might well be of value for explaining the wider context and vision. However, too often the effort of communication is mistaken for the actual impact that has been achieved. It’s easy to fool ourselves into believing the job is done because we have deployed a tool we have the competence to use.

This is where the act of listening becomes such a useful weapon. Deep listening is an underrated skill. The act of noticing what is happening, even when it might contradict what we might want to hear, is a way of understanding a system with less attachment to what is wanted and more capacity to accept what is actually going on. As Alan De Botton said:

‘Good listeners are no less rare or important than good communicators. An unusual degree of confidence is the key — a capacity not to be thrown off course by, or buckle under the weight of, information that may deeply challenge certain settled assumptions. Good listeners are unfussy about the chaos which others may for a time create in their minds.’ (Alan do Botton)

The fundamental difficulty in listening is to hear things which contradict our own view without immediately rejecting them. The ability to suspend judgement and tolerate information that challenges our own beliefs is rare. However, when we manage to achieve this our understanding deepens, we are equipped with information we might have lacked before, we are forced to confront our preconceptions and entertain the possibility we could be wrong. A difficult task for our egos, particularly if your job title implies that you are in charge.

When we work with what actually ‘is’ we become more effective, we have stepped into the messy but potentially transformational space of dealing with reality rather than an idealised fiction we might prefer. Which of these has the greatest likelihood of success in culture change? The answer isn’t hard, however, the apparently simple act of listening is. To be continued in the next blog.