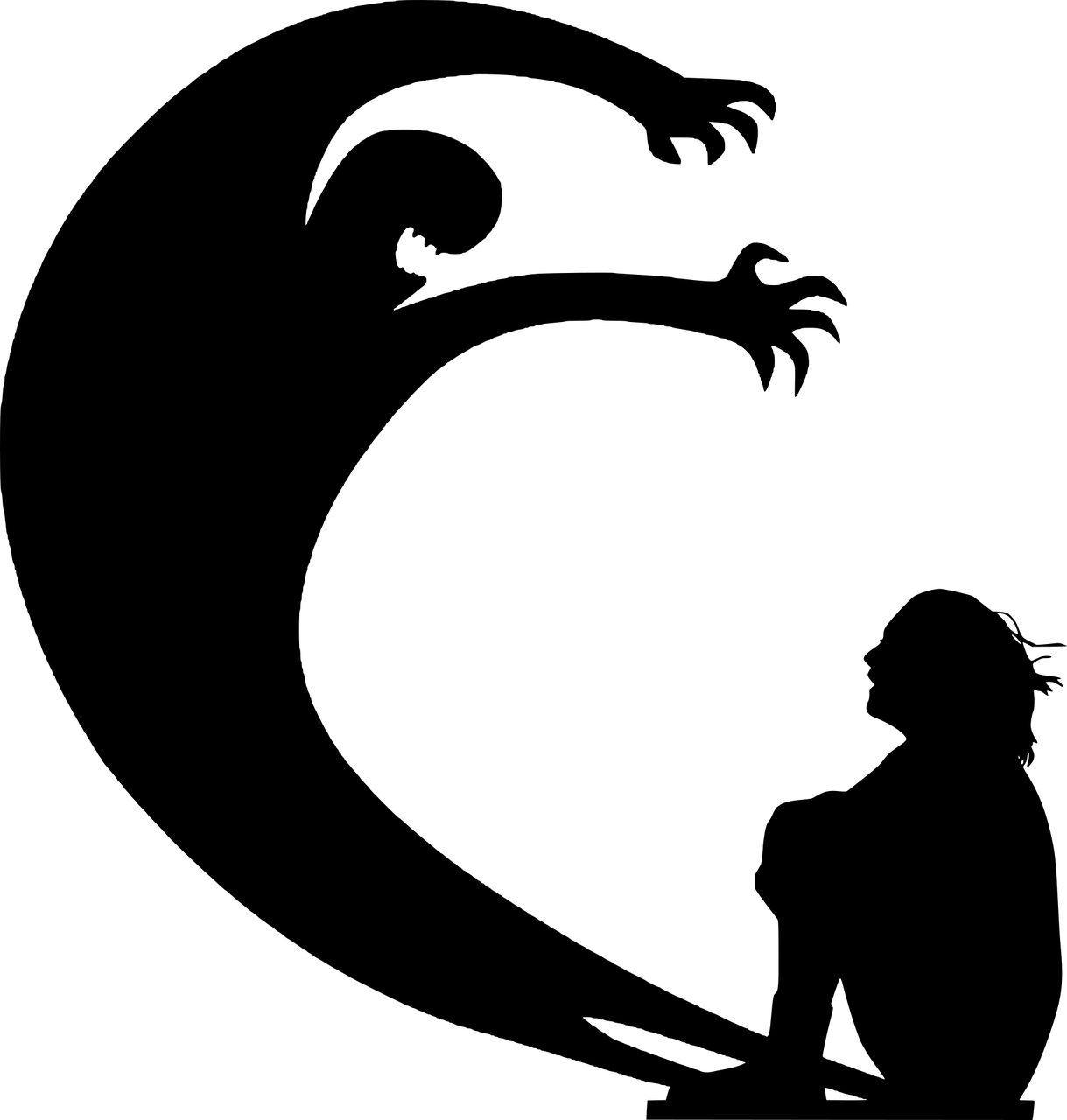

Anxiety

Asher Rickayzen • May 7, 2020

During lockdown, I have been appreciating the blogs I regularly read even more than usual; possibly because I am less rushed and have more time to concentrate on them. One of them written by the excellent Naomi Stanford says:

“What I’m not seeing much of in my day-to-day work is organisational leaders consciously and reflectively discussing and debating these larger questions (about what the future could look like). What I’m seeing is a bias to action to get things ‘back on track’, in much the same way as they were pre-Covid-19.”

For my part, what I’ve noticed in my day-to-day work is the lack of conversation about the anxiety we are feeling and I connect this with the bias to action. I don’t believe there is anyone who is not in an increased state of anxiety for some reason at the moment; it’s a separate question as to whether we recognise it in ourselves and each other. This is a peculiar lesson I have learned for myself about anxiety through adopting the process of morning pages; anxiety is not necessarily easy to spot nor are the ways in which we try (often subconsciously) to free ourselves from the inner discomfort it brings.

I’m not criticising the need for action, there are some very big and demanding tasks which need be done. You might well ask, with such daunting tasks to face, why does an awareness of anxiety matter? Surely at the moment the task is everything? It matters now for the same reason it always mattered, and that is because without healthy relationships and minds everything we are setting out to do becomes more challenging. Our behaviour can be distorted by our unconscious need to rid ourselves of anxiety. We might achieve less at the very time, as a society, we need to achieve more.

Unexpressed anxiety often reveals itself in ways that are not obvious, such as the desire for control or perhaps blaming others or asking questions which are impossible to answer. I see these quests for certainty as a search for the antidote to the huge uncertainty which hangs over us all. Our capability to deal with uncertainty is more valuable now than ever; we had better take the opportunity to learn more about how to develop it.

It isn’t surprising overt conversations about anxiety are missing in organisations, it’s only natural. After all, wouldn’t most of us prefer to wrestle with those things outside ourselves which may be hard but are in some ways tangible, that we might stand a chance of ticking off on our to-do list, rather than attempt to address the tangled mess of semi-formed thoughts and complicated feelings that constitute our anxiety?

On top of that difficulty, a conversation about anxiety takes a huge amount of courage born from a display of vulnerability; at its heart it is admitting publicly we are frightened. This is impossible to manage in any environment that doesn’t feel exceptionally safe from a psychological perspective. It becomes even less attractive as a course of action when we are attempting these topics on a video-call, with the inherent risk of the screen freezing at a crucial moment or the dog bounding in to demand feeding.

The thing we most want – reassurance – cannot be provided. The next best thing we could do is talk about our fears. What I’m not seeing very much are the real conversations needed because the task (the bias to action) provides such an apparently reasonable reason for avoiding doing so.

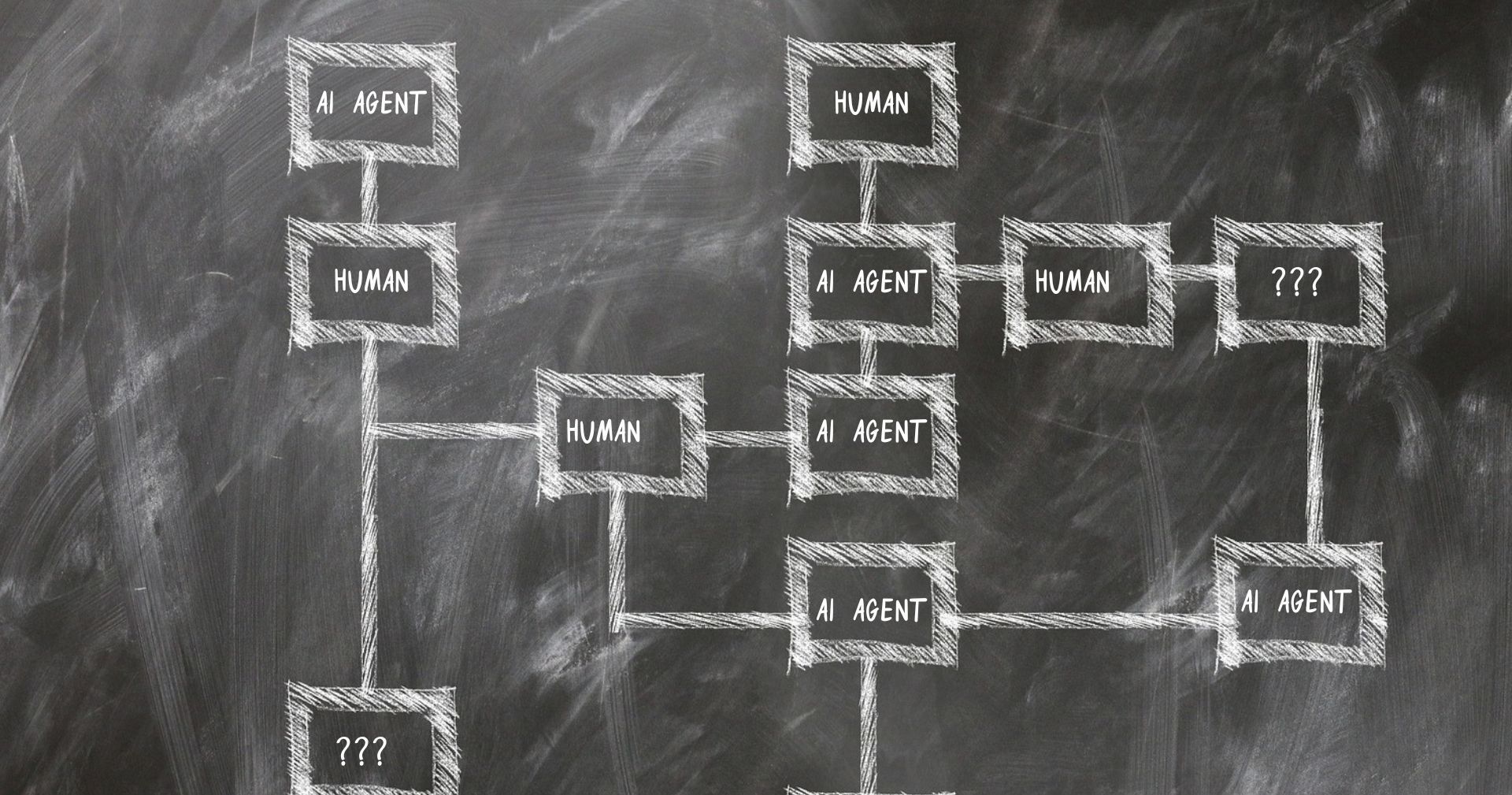

It’s just over 3 years since ChatGPT was released and LLMs were suddenly a dominant topic in organisational life and society more broadly. A tiny period of time, during which their capability has evolved at a fearsome rate and organisational culture has struggled, and largely failed, to keep up. Only this week I’ve noticed two large organisations I work with just reaching a point of issuing guidance about the use of AI chatbots in two particular aspects: one forbidding the entry of company information in employees’ personal AI chatbots and another banning the use of those AI chatbots that join online meetings to take notes (which I’ve always considered very sinister so I’m glad!). As always, cultural change lags far behind the speed of technological change, throwing up many challenges and paradoxes. Another handy illustration from this week was a client of mine being simultaneously criticised by one cohort of their customers for using AI in their work, while another group of their customers was criticising them for not using AI enough. It’s the wild-west at the moment as we learn our way into the future. You need your wits about you, it’s a truly fascinating, complex time. An analogy I have begun to use which helps me make sense of what I see happening in many places and to explore the topic with my clients is the following. Imagine a candle-making factory in the very early days of electricity becoming widely available. The owner of the factory employs six workers, one of whom has the role of holding up a candle so the other skilled craftsmen have enough light to perform their tasks. When the owner of the factory hears about electricity he concludes the biggest opportunity he has is to install electric lighting, thereby eliminating the need for one sixth of his workforce and reducing his costs accordingly. There are many bigger questions he doesn’t ask himself about the future of candles or the opportunity for wider change in his own process. And, from his somewhat remote ownership position he is not aware that most of his candle makers have secretly been bringing electric torches into the factory for a while as their way of helping themselves to do the job more easily. They have been engaged in ‘productivity secrecy’ for fear the owner would disapprove. They already have learned far more about what electricity can (and just as crucially can’t) do through their first-hand experience than the owner has gleaned through his own means. I’m seeing this again and again. A scramble to set AI direction at the top of the organisation with many unconstrained (and sometimes dangerous) experiments going on at grass roots. I’m sure there is much else happening between these two positions, including the usual middle-management struggles of trying to bridge the gap and convey often non-sensical messages. If you happen to read this blog and would be willing to share your own experiences or your own metaphors or you see ways of extending the candle-maker analogy I would love to hear from you: asher@seemoreconsulting.co.uk . [This blog was entirely hand-crafted using the original AI (Asher Intelligence!) and there is nothing artificial about it. However, the picture was generated using Nano-Banana which yet again has astonished me with its speed and capability]

I’ve noticed an almost audible sigh of relief when teams feel able to talk openly about disagreements and misalignment. Unstated misalignment is both a nagging worry and an obstacle to trust. Perversely, openly exposed misalignment creates a stronger sense of shared hope and strangely … alignment. That feeling of not being alone, even if it’s not being alone with a sense of misalignment is a valuable way of feeling more connected. Alignment is never a permanent state, and even in situations where there is a belief that alignment exists, the probability is that with deeper examination or a wider field of vision, there will be areas of undiscovered disagreement and misalignment. There are two golden rules that I find helpful to remember and remind teams about. Firstly, that alignment is a process (i.e. a dynamic state) not a static destination. Secondly, the natural order of things is that whatever alignment exists it decays and this is accelerated in teams that work separately for much of the time, particularly when everyone is busy; you will probably recognise these as features of nearly all teams. The world isn’t static, things change and, therefore, alignment is always going to erode. Accepting these rules is helpful because they reduce the disappointment teams often experience when they see misalignment as a sign of failure. It might feel unnatural to accept this, but it’s far easier to do the hard work of building alignment – involving as it does courage, vulnerability and commitment to ‘go there’ – without the additional mental burden of inadequacy. The need for this process of aligning will never disappear. The struggle for alignment has many worthwhile pay-offs. Teams with higher degrees of alignment can work more quickly, recover from set-backs more readily and enjoy a more productive working environment. The skill is avoiding the false comfort of believing the Holy Grail of permanent alignment can ever be found.

It’s long been my habit to begin the day with a walk whenever possible; it’s a gentle way to get mind and body moving (and yes, I know I’m privileged to have the space and time to do this). What’s changed recently is that sometimes—not always, because usually I want to hear birdsong —I take AI along as a companion. I hadn’t realised the power and ease of simply talking to it in voice mode. I suspect that when I look back in six months I’ll find it hard to imagine there was ever a time I didn’t know about this. Perhaps some readers will roll their eyes at my late-to-the-party discovery. I now have conversations with ChatGPT as I walk, speaking into my AirPods, letting it help me develop my thinking. It’s supportive, creative and occasionally sycophantic (which has its charms). It doesn’t get bored. It helps me bounce around fragile ideas and unformed thoughts; I generate more value than I do when I think alone. And because the conversation is captured, I don’t have to worry about the practical side of note-taking or remembering everything. What’s struck me most is how different a voice conversation feels compared to the written kind. It’s oddly difficult not to imagine the AI as sentient—the rhythms and reactions feel so familiar, so human. This morning one thought landed with some force, which seems blindingly obvious now: just twelve months ago, I couldn’t have imagined working this way. That led me to new questions about the impact of AI on organisational strategy, culture and leadership: If you were starting a business today, with AI already part of the world, what would you offer? How would you organise? How would you design your processes? What human roles would you need and what could AI do instead? What’s the role of the human being in that business—and where can they add the most value? What would it take to move from “business now” to “business + AI”? It feels analogous to the arrival of electricity. To imagine running a business with electricity, while still living and working in a world built without it, was a vast leap; maybe impossible. What fascinates me most—reinforced recently in work with a large tech company, ironically right in the heart of AI-land in Silicon Valley—is how rarely these fundamental questions are asked. The scramble to meet today’s demands leaves little space for reflection. Yet, as Margaret Wheatley put it: “Without reflection we go blindly on our way, creating more unintended consequences.” I’ve long believed that reflection is a profoundly human quality, one AI cannot emulate. And yet, perhaps that’s simply a limit of my imagination. This brings me back to the electricity analogy. On a recent trip to Spain, I arrived in the middle of a nationwide power outage. Suddenly all the things I normally take for granted—making phone calls, going online, paying with a card, withdrawing cash—were gone. When society has been built around something, its absence reveals what we’ve forgotten, or perhaps never learned, to do. In my case, even writing down the address of my accommodation instead of assuming my phone would tell me. That, I think, is the warning for us with AI. As we build our world around it, we will inevitably lose some abilities we now take for granted. The one capacity we must not surrender, though, is the most human of all: the ability to think for ourselves.

At a webinar I participated in on organisational culture earlier this year, it occurred to me that a topic which was notable through its absence was AI. There were several hundred participants from organisations across the world of all shapes and sizes, but not a single question or comment about AI. This surprised me. I find it difficult to imagine that an event with broad representation on any other topic would not include a significant amount of coverage for AI; in fact, in many cases I think it would be the dominant theme. Why was this? There could be many reasons but I suspect we still see human beings as the prime carriers of culture and are not thinking about the way in which AI is currently (and will be more so in the future) a carrier of culture whether we are aware of it or not. In addition, I think we are typically talking about AI as a tool in organisations more than a transformational force which inevitably will have a huge impact on culture. I’ve also noticed in my interaction with executive teams over recent months that the extent to which AI was being discussed appeared to be very small. It could, of course, have been taking place at times when I’m not present but my enquiry into this with the Global CEO of a large organisation I think was illustrative of another point. ‘Do you talk about it much?’ I asked. ‘The CIO raises at times but we change the subject quickly.’ was his reply. Not surprising really; in the same way as many large technological transformations from the past were, they are seen too easily as being the domain of the technologists and not something of much broader potential (and concern). And this at a point in time when I would guess that at least 60% of the employees in most organisations are using AI daily, even if it’s on their phones (if they don’t have access on their computers), to help them handle their workloads, find out information, produce first drafts and so on. So on the one hand, AI is in use everywhere and on the other, I don’t think we are consistently having the level of conversation we should be having about the implications for organisational life. Those of you who know me, know my interest is the interaction of strategy, culture and leadership. Just to get things started, here are a few of the questions I think we should be asking to build our level of awareness and preparedness for the organisation of the future. Strategy What new capabilities, which have been prohibitively expensive or difficult for us in the past, can we acquire through AI? What do we want our organisation to look like in terms of the balance between human workers and AI agents? What do we do for our customers (which they value) which they can now do for themselves through AI? Where is it essential for us to maintain or introduce the human touch? Leadership How do we lead mixed teams of human and AI workers? What skills do we now need that weren’t necessary before in terms of AI knowledge and capabilities? How do we create an environment of psychological safety when jobs are threatened (or already disappearing)? What is my role as a leader in terms of protecting the organisation from AI, connecting the organisation to the possibilities of AI, promoting the necessity of us understanding and adopting AI (even though it might threaten our roles – see the previous point)? Culture How do we ensure our AI agents have consistent values with those of the organisation? What are the skills and behaviours we most value now, how will this change and how do we help people adapt? How do we teach our AI(s) the desired culture of the organisation? Whose values are we unwittingly adopting through the use of the AI systems we choose? What is threatened by AI in our existing culture that we want to maintain? How do we evolve a culture which embraces (or accepts) AI fully? Questions for everyone Who do we trust & what is the truth? What do we want work to look like? How will organisational ‘nous’ be acquired when a high proportion of entry-level white-collar jobs have disappeared? Not easy questions. But as with all transition points, it’s far better to face them now than to avoid them and discover in the future we have created organisations that fail to meet the standards we want.

I am about 18 months into my personal use of AI tools and I’m beginning to notice some of the ways in which it is impacting on me. Productivity for me has increased massively in some areas and diminished substantially in others. In particular, I have noticed a reluctance on my part to engage with writing and video (animation) production. Firstly, on the productivity side, I have found AI fantastic at helping me get started on projects, acting as a form of second memory, improving my emails, generating images, suggesting ideas, creating copy, interpreting complex documents, advising on topics I know nothing about … all the things I imagine most users are doing with it. I’ve enjoyed experimenting (unsuccessfully) with vibe-coding and (also unsuccessfully) with creating AI agents to speed up my daily handling of emails. But on the reduction in productivity side of the ledger, I notice that in some ways I have become lazier and disincentivised from doing things for myself because it’s so easy to reach for AI. When I use AI to produce meeting notes for me (if for example I’m on a video call) it is extremely handy, it saves time and the quality is generally good. However, the cognitive experience is entirely different from me taking my own notes. When writing my own notes, I notice my engagement in the conversation is better (I would have thought it would be the opposite given that I could relax into the content but it just isn’t) and I have to mentally process differently which means I remember more of the conversation and have a deeper sense of connection with the content. Knowing I don’t have to rely on myself (because AI is working away in the background) is in many ways a blessing but in others an obstacle to overcome. On the creativity front I really notice a big difference. What happens now (as opposed to before the point AI became part of my life) is that I think about what I want to create, I get excited about it, and then the thought enters my head that AI will do this better than I do and (perhaps more importantly) it will do it without me having to invest any effort in it at all. At which point, all my enthusiasm drains away and I don’t progress the idea at all. I would not have predicted this would happen. (As an aside, there is also a slightly different version of this: where I start something but don’t finish it because I know that I can always use AI at some point in the future to tidy up the whole thing for me.) It was fascinating when I met someone recently (a senior executive who is responsible for the introduction of AI in their organisation) who said she had been reading my blogs before our meeting. My first reaction was one of embarrassment because prior to this blog, I haven’t written anything for a couple of years. But I relaxed when she said she had enjoyed them because she had ‘heard your [my] voice’. I had always found AI to be extremely helpful in getting over ‘blank-page syndrome’; i.e. overcoming the intimidating hurdle (at least for me) of starting from scratch. She then went on to describe how she was using AI herself and in her process she always ‘went through the grind of producing the first draft’. She then used AI to coach her on how to improve it and to point out blind spots. I am really attracted to this alternative mode of deployment and will be experimenting with it over the coming weeks. If there is anyone out there who reads this blog and is over the age of 40 and remembers Queen’s (a rock band) albums in the 1970s, they used to state on the cover that synthesisers were not used in the production of their music; i.e. it was produced on guitars, keyboards, human vocal, real drum-kits. They clearly felt that by doing this they were adding to the quality and perhaps authenticity of their musical production. This is analogous to the point I’ve reached with AI. I want to return to my original sound and rediscover my voice. So here it is, ‘unsynthesised’, human-generated, free from AI of any sort … all my own words! Welcome back.

In 2009 I left corporate life with very little idea of what I wanted, or indeed would be able, to do next for a living. It was an uncertain and scary time for me, a core part of my previous identity – an executive in a large organisation – had been swept away and my new one was unknown to me. It was a liminal state; one which I did not enjoy. In theory it was a time of possibility and reinvention, of freedom, of the chance to try something new. All of which was well and good in theory but inner doubts – amplified every time well-meaning friends asked me ‘what are you going to do next?’ – provoked strong feelings of disquiet in practice. The one thing I could latch on to was the ambition to run a business from a shed in the garden. It was an appealing prospect to me – years of commuting to be replaced by a stroll down the garden path. I wanted the business (whatever it was) to be really small (‘almost insignificant’ was the mantra I had in mind) and agile, and yet to work with much larger entities. I did not know what the business would actually do, just that it would be run from a garden shed. Luckily, I had a shed in the garden; unfortunately, the shed was somewhat dilapidated, lacked the basic office comforts of heating, insulation, light, a desk, a roof that didn’t leak and many other things. However, this provided the opportunity for me to get stuck in to a renovation project, a project that at least provided something tangible as a goal and provided a stop-gap answer to that ‘what next?’ question I had begun to dread. The renovation began and much to my surprise, about 5 months later, it was completed. I was the proud owner (and builder) of a spruce, comfy shed-office with a floor, a roof, heating, lighting, insulation, a desk and (wonder of wonders at that time) WiFi! To anyone experienced in DIY or construction, I imagine the task would have seemed trivial; to me, every part of it felt daunting. I persisted, I sought advice, I made mistakes, I corrected mistakes. The project was complicated (for me) but I knew it was possible, evidenced by the fact that there was nothing unique about it and that if I got stuck I could ask someone with more expertise and I would find the answer I needed. I contrast that with the building of the business which is now run from the shed. Once I had overcome the initial hurdle of not knowing what the business was going to do, there was no guaranteed playbook I could draw on for bringing it to fruition. There were a multitude of opinions, at times an overwhelming number of choices and decisions, but nowhere was there the formula for making the business I wanted to work at the particular time I was trying to do it. The path involved experimentation, adapting to changing circumstances, making decisions in the absence of meaningful data, all of which often felt like a high-stakes guessing game. It has been a learning journey, rather than a planned and deterministic one. Looking back from the present, it all makes perfect sense, but repeating the same steps again would not necessarily result in success; the context is different, nothing ever stays exactly the same. The renovation of the shed and the building of the business have both required resilience, albeit in different forms; they both taxed me. But one fundamental difference between the two of them was that I knew if I persisted I would eventually complete the shed; there was no such certainty with the business venture. The weight of uncertainty was tiring at times, provoking anxiety and a yearning within me to ‘know’ it would be ok at a time when this just wasn’t possible. Through my work as an executive coach (the business which emerged in the shed) I frequently observe the reluctance to engage with complexity in the organisations I work with, a reflex to reduce a situation to a state that feels more manageable and controllable; a situation in which existing knowledge can be re-applied. Often this simplification is more to do with an unconscious desire to escape the anxiety caused by uncertainty rather than a purposeful attempt to tackle the situation effectively. Some situations by their very nature are complex: they lack cause and effect, they are entangled, they are unpredictable. I love the words attributed to Albert Einstein: ‘Everything should be as simple as possible but no simpler’. When simplicity is a form of avoidance it does nothing except to reduce fear at the expense of understanding; the understanding which might make all the difference to the effectiveness of what gets done. Renovating the shed showed me the power of a clear plan and steady progress. It also gave me the chance to reflect whilst at the same time feeling I was doing something productive. Building my business taught me the art of navigating through uncertainty. Both of these are necessary in the world of business, let alone life; perhaps the critical skill is choosing which approach should be applied to the situation being faced. As I sit in my shed-turned-office working with clients, it serves as a constant reminder of these distinct experiences, each valuable in its own right.

Imagine the following seemingly impossible challenge: an organisation of 60,000 people, with no hierarchy, leadership, authority figures or plan, acting in a coordinated, synchronised manner, with large amounts of collaboration and adaptability, without any instructions in any form being issued at all. To make it worse, very few of the people involved know each other, many speak different languages, they come from diverse backgrounds and there is a very wide range of ages and physical abilities. Tough to imagine achieving it isn’t it? But while I was watching a sporting event last week (the St Louis Cardinals were playing the Chicago Cubs at baseball) this is exactly what happened in the form of a Mexican Wave which broke out at various points around the stadium and seemed to flow effortlessly around the crowd, transferring seamlessly between seating sections, moving in harmony between upper and lower tiers and hopping gangways with ease. It made me think about the way we might set about organising this task if we were asked to do so. I would instinctively want to create plans, a budget, a selection process, structure, briefing sessions, training etc. All the things I often associate with change and organisational life. The Mexican Wave demonstrated to me that there is something innately possible in groups that we often suppress or obstruct through the very things we believe will allow effective action. The desire to control, rather than encourage or harness what might naturally happen, is strong! A different mindset and approach that comes from complexity science, a school of thought which reflects the world as it is rather than what we would like it to be, (I will write more about complexity science in a later blog) is a richer way of seeing things. It is striking how often I hear people lament that their organisation is adept at coping in a crisis but how slow and rigid things are in ‘normal’ times. There is a longing for the mindsets and behaviours which are adopted naturally during a crisis – such as faster decision making, more direct conversations, a willingness to quickly adapt and learn, a tolerance for mistakes – to be harnessed all of the time. What is it about a crisis that allows this? Certainly there is often more focus around a single objective, the fog of competing priorities if often lifted and this alone has a significant impact. But I also think our mindsets about complexity, although not expressed in those terms, has an equally important part to play. There is a much greater level of acceptance for the need to self-organise (in the same way the crowd performing the Mexican Wave self-organised) and the bureaucracy of traditional hierarchical power is temporarily pushed aside – there often isn’t the time for it or the means to control things. We know in a crisis we are treading novel ground and we trust an ability to improvise (or make it up as we go along); there are no obvious answers, only tough dilemmas. In a crisis it is less clear what ‘good’ looks like; it’s usually a matter of noticing whether an action makes things better or worse and adapting accordingly. In reality, we improvise our way through every situation, crises simply remove the pretence that life can ever be any different from this. We know we can never predict exactly what will happen, denying ourselves this or believing it can be avoided, simply causes us to act in ways that are not helpful. In a crisis there is a tacit acknowledgement that ‘self-organising’ is essential and more latitude is given (usually quickly and informally) to enable this. Sometimes this is explicit, take for example the statement by the CEO of Walmart in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the storm which destroyed much of the infrastructure in huge swathes of New Orleans. He made it clear to all employees in the locality they were empowered to do what they felt it was right to do at the time and he would back them unreservedly with any action they took; acting in an unequivocal way to make the conditions for experimentation and improvisation safe. Walmart were able to assist the local community much more effectively than many of the government agencies, which were hidebound by process, control and quite possibly the fear of being criticised (which they received in any case because their response was so slow). The capacity for self-organising was demonstrated in abundance during the pandemic. Traditional command-and-control structures and processes were rapidly diminished yet organisations adapted at great speed to the evolving demands of working from home and the many other challenges faced. There was no overall master plan yet organisations, by and large, managed to provide the services they had been providing prior to the pandemic through lots of adjustments to working patterns, relationships and processes agreed at a local level at speed and which amounted to something large and relatively stable, rather like the Mexican Wave. It’s no surprise then that this seems to be the philosophy in the military where as much autonomy is given to local units and the role of the centre is to support what they need rather than tell them what to do. Relinquishing control to those closest to the day-to-day operations, who are in a much better position to assess the situation and make decisions, makes logical sense but challenges many traditional views of heroic leaders who think their role is to know what to do and issue commands to obedient followers. During a crisis we are much more likely to reduce our attachment to ‘the way things should be’ and are much more willing to accept and adjust to ‘the way things are’. The pomp, circumstance and trappings of organisational life are a luxury which cannot be afforded during crises and when stripped bare it’s surprising how an entirely new capacity for change can emerge. It’s also noticeable how quickly we forget this when the opportunity for business-as-usual returns.

I worked for many years with someone who was the most powerful listener I have ever experienced. He possessed a rare combination of paying full attention to whatever you were saying and resisting the urge to add his own views and beliefs. He listened with the attention a cat gives when stalking its prey; in that moment nothing was more important, nothing was allowed to distract. The quality of his listening affected the quality of my speaking; my words felt important, each one treated as precious. It’s a small step to take from feeling your words are important to feeling you matter. Being made to feel you matter … what a wonderfully affirming act. He made me feel heard in a way that felt rare to me. It had the impact of saying much more than I intended. I found myself disclosing information I didn’t think I would; sometimes the information I disclosed was new to me. I found myself saying things I hadn’t voiced before, in the process learning something about myself. This was often enormously helpful; his listening allowed me to understand my own thinking much better than when it was trapped silently in the echo-chamber of my thoughts. Then when I thought I had said it all, when I didn’t think I had anything left to say, he would replay what he had heard or ask a simple question, validating my thinking, proving that he had listened, allowing me to change something (often important) in my views which had, until that point, felt so firm. You might be rolling your eyes at this point, the importance of listening is obvious isn’t it? Wasn’t it covered comprehensively on the first management training course anyone ever attended? Yes and no. It is obvious, we know it’s important but that does not necessarily mean we do it well. Common practice is not the same as common sense. How accurately do we evaluate our own capability as a listener? How strong is our belief in the immense value it can bring? Most of the time we assume we do it well, rather like our belief that we possess a good sense of humour and are above-average drivers; we tick the mental box and move on. There is a further step that can amplify the impact of listening in organisations – action. The evidence that our words are important to leaders is reinforced when we see something happen as a result. However, there is a twist best exemplified by a version of the following slogan I often see: ‘you said, we did’. In many ways this is powerful, an articulation of the importance of speaking up and being listened to. But the danger is that it reinforces the thing most modern organisational cultures want to escape – the parent-child relationship which is the antithesis of empowerment. Once my colleague demonstrated he really understood my perspective, his great skill was to resist the urge to resolve things for me. At first, I found this deeply frustrating; he was more senior, he had more power to change things, why didn’t he step in and sort things out? I guess because he understood that by doing so he would be limiting my development, my growth and my ability to create change. Isn’t this what we want? To feel empowered. Think how powerful it could have been if all my colleagues had shared a similar experience and the whole organisation was populated by people who felt as I did after being listened to. In the previous blog I wrote about the difficulty of bringing about cultural change in complex systems, i.e. organisations, and the value of disturbance as a catalyst for change. The form of listening I have described here is in itself a disturbance; it has the potential to be transformative individually and even more potential collectively. In many organisations, hierarchy, fear, our egos and general busyness are barriers to paying attention; the seemingly simple act of listening can take some doing. But who knows where it might lead? ‘Big doors swing on small hinges’.

Experiences of working with different organisations on cultural change have underlined the intimidating scale of the task. I often hear comments from leaders such as: ‘It’s too large to seem possible’; ‘We need a big outcome, we don’t know where to start’; ‘We’ve made so many attempts in the past that we’ve lost belief in the approaches we use’. One of the things which exacerbates the situation is that by regarding organisations as machines (a common metaphor), and regarding change as a mechanical, predictable process, we become despondent when we discover it just isn’t like that, ‘the map is not the territory’. It isn’t simply a matter of defining what is wanted in terms of culture, communicating it, issuing instructions and then watching it happen. It’s more helpful to accept organisations for the complex systems they are, given that getting anything done involves a multitude of small human interactions combining in ways which are unpredictable and uncontrollable. We live our lives in ‘the territory’, however different it is from the map we might have expected. The characteristics of complex systems require a willingness to relinquish the belief you can control what happens AND at the same time hold on to the possibility that systems can reach a tipping point in terms of change; sometimes actions which are seemingly small can enable new patterns (i.e. culture) to emerge; what we don’t know is when or how this will happen. This is challenging to leaders who often believe, and are rewarded on, the ability to control. As a colleague of mine used to be say, ‘it’s tough to be in charge but not in control’. Complex systems do not lend themselves to predictability, but on the other hand small actions can become amplified and disturb embedded patterns behaviour; the frustrating part is not knowing which of these might produce the desired effect, hence the need to try things and to notice with great attention what the impact is. If the impact moves things in the desired direction culturally then you know to do more of it. If on the other hand the impact does not, try something different. An example of a cultural tipping point being reached was the introduction of the 2p charge in supermarkets for plastic carrier bags. It was an experiment, the brave step of trying something different, which has drastically reduced the number of plastic bags that are in circulation. Who would have thought such a massive impact, which has transcended geography, socio-economic class and age could have been achieved through such a seemingly insignificant change? You never know what the difference will be that will make the difference. Much organisational change energy is devoted to the communication of change in the form of announcements, internal publicity campaigns and training. This is understandable given that it is something we can control, perhaps in this way making us feel more powerful as leaders. This might well be of value for explaining the wider context and vision. However, too often the effort of communication is mistaken for the actual impact that has been achieved. It’s easy to fool ourselves into believing the job is done because we have deployed a tool we have the competence to use. This is where the act of listening becomes such a useful weapon. Deep listening is an underrated skill. The act of noticing what is happening, even when it might contradict what we might want to hear, is a way of understanding a system with less attachment to what is wanted and more capacity to accept what is actually going on. As Alan De Botton said: ‘Good listeners are no less rare or important than good communicators. An unusual degree of confidence is the key — a capacity not to be thrown off course by, or buckle under the weight of, information that may deeply challenge certain settled assumptions. Good listeners are unfussy about the chaos which others may for a time create in their minds.’ (Alan do Botton) The fundamental difficulty in listening is to hear things which contradict our own view without immediately rejecting them. The ability to suspend judgement and tolerate information that challenges our own beliefs is rare. However, when we manage to achieve this our understanding deepens, we are equipped with information we might have lacked before, we are forced to confront our preconceptions and entertain the possibility we could be wrong. A difficult task for our egos, particularly if your job title implies that you are in charge. When we work with what actually ‘is’ we become more effective, we have stepped into the messy but potentially transformational space of dealing with reality rather than an idealised fiction we might prefer. Which of these has the greatest likelihood of success in culture change? The answer isn’t hard, however, the apparently simple act of listening is. To be continued in the next blog.

A question I have frequently been asking leaders over recent months is to describe how they see their role. Specifically, do they see themselves as a protector or a connector?* The distinction being that a protector is concerned about shielding others from the world out there with all its itinerant uncertainties and mess, whilst a connector is concerned with exposing others to it and connecting them as widely and deeply as possible. The first assumes (tacitly) others are not capable of navigating it; the second, that unless they learn to navigate it the organisation will fail. When the pandemic barged its way into all our lives in 2020 it proved conclusively to me that our ability to cope is far greater than might have been inferred previously. People innovated, made local decisions, juggled priorities and generally responded in ways that could never have been imagined. So why do I frequently experience leaders who are stopped in their tracks by the question, pausing and then responding in a way that indicates a desire for post-pandemic ‘real-life’ to resume, which naturally invites them to fulfil the role of protectors. It is interesting to ask at what level of seniority, pay or age do we assume others are just as capable of handling reality as we are? A protector mindset might, for some, be founded in an ‘information-is-power’ mentality but in my experience it is much more frequently driven from a very positive motive of care or an assumption that ‘this is what leaders are paid to do’; keep it simple and orderly or people will become confused, or they might lose focus or perhaps worry too much or be downright paralysed by fear. But if you can cope why can’t they? What gave you the capability they lack? Possibly it was the simple act of exposure. On the other hand, isn’t the position of connector irresponsible and lazy? Doesn’t it transgress the fundamental role of leaders in providing clarity and reassurance. Shouldn’t leaders have the answers? Yes, there is truth in this and yet we all know every time we see the news that the world is inherently unstable and complex, and pretending the organisations we work in are immune is optimistic thinking at best and a delusional at worst; a delusion that means we cling to practices that no longer serve us. The middle ground is the interesting space, where beliefs and values get tested. What sort of information do we withhold and what do we share? What principles do we apply in making that decision? Who do we typically protect and who do we typically connect? Fruitful territory for understanding more about our opaque inner-worlds. When you add up all these protector mindsets you get the very thing most organisations declare themselves as not wanting … a parent-child culture. Empowerment is recognised as a necessity in organisations that want to be agile and customer focused, but empowerment without transparency is like Ernie without Eric, it just doesn’t work. (I imagine this is a meaningless metaphor for anyone in gen y or z so here is a link which might explain it). We bemoan a lack of accountability, insufficient agility, lukewarm innovation, decisions forever being escalated. So how do you see yourself, protector or connector? ____________________________________________________________________________ * My mental image of a protector is that they slam the office door behind them as they enter the room, breathe a sigh of relief and hope their words of calm authority distract us from those glimpses of the chaos out there.